US Release: 12/1972 (Motown M758)

UK Release: 3/1973 (Tamla Motown TMSP1131)

Chart Positions: US Billboard Pop #1 US Billboard R&B #2 Canada #5 Australia #43 UK #50

Singles Released from Lady Sings The Blues – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

US Release Date: 12/1972 (Motown M1211)

UK Release Date: 3/1973 (Tamla Motown TMG849)

Chart Positions: US Billboard Adult Contemporary #8 US Billboard R&B #20 US Billboard Pop #34 Canada #44

“When the announcement was made that I would be playing Billie Holiday, my mere acceptance of the role sparked a great deal of criticism….We hadn’t even started shooting and the press had already turned against me.” Diana Ross – Secrets of a Sparrow

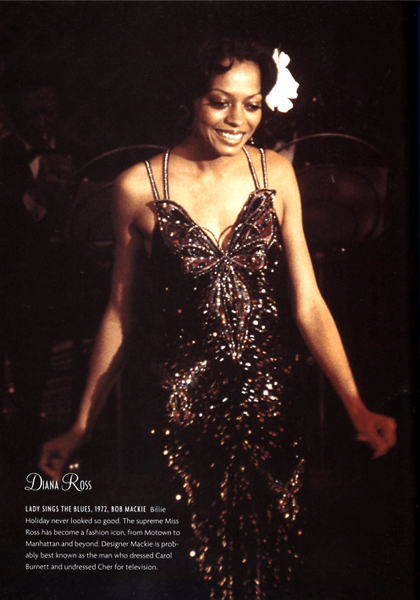

Having shown her impressive and versatile talents in her first solo television special, Diana!, including a natural flair for comedy and mime, Diana landed a far meatier role in the feature film Lady Sings The Blues, portraying the legendary jazz/blues singer Billie Holiday. A total contrast to anything she had tackled before, many critics had reservations about her taking the role before the movie had even hit cinemas. Being her first movie, Diana eagerly set about silencing the critics. The results were truly stunning. She far exceeded all expectations, excelling in the role and earning wide critical acclaim for her powerful performance, which was both harrowing and compelling. Showered with awards, including a Golden Globe win, she also deservedly received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress plus a BAFTA (British Academy Award).

Prior to the release of the film, Motown issued a double-album soundtrack, which served as an effective trailer. The quintessential and divine soundtrack captures some of Diana’s most challenging vocal performances. Critics and die-hard Billie Holiday fans had some qualms about her singing Billie’s songs, as vocally and physically the two artists bore little resemblance. True, there were many differences between Diana’s angelic yet soulful and often anguish-filled vocal style and the starker, husky, blues-tinged voice of Billie Holiday. So, it’s to Diana’s credit that she never once tries to emulate Billie’s sound, or, as some sneering critics predicted, deliver a Supremes-like performance. What she did do was embody the spirit, timbre and nuances in Billie’s vocal style, shrewdly encapsulated with elements of her own sound.

Diana Ross recalled in her autobiography Secrets of a Sparrow: “During my nine months of research, I made some important decisions…one of them being that I would not try to sound like Billie….I would work to bring through my own sound. Strangely, since I listened to almost nothing else during that time, I took on the same phrasing she used, and in this way, I ended up sounding a lot like her after all.”

Diana digs deeply away at the material, relying on her acting skills to interpret the lyrics astutely, as though she had lived through all the pain and suffering that marred Billie’s short and tragic life. She captures the moods of the songs perfectly, and they emerge as unique and distinctly Diana Ross without losing the depth, spirit and often dark moods of the original recordings.

For example, she commendably captures the flavour and feel of the breathtaking Good Morning Heartache. The deep wells of emotion, loneliness and acute vulnerability expressed by Billie on her recording is given a noble and definitive working-over. Recorded by Billie in 1957 for her Solitude album and written by Irene Higginbotham, Erkin Drake and Dan Fisher, the song was later recorded and released by Motown artist Billy Eckstine.

When the song was chosen to be Diana’s next single, a lot was riding on it, as she hadn’t had a major hit since 1971’s Remember Me. Sadly, it failed to make the grade and stalled at a disappointing #34, probably as the pop radio stations didn’t give it much airplay. On the other hand, R&B stations were much more forthcoming, and it glided into the R&B chart at #20 and landed in the Top 10 Adult Contemporary. A masterpiece in itself for sure, despite its lack of mainstream chart success.

A second single was initially scheduled, but owing to the lack of support for Good Morning Heartache, these plans were swiftly dropped. It was set to have been the exhilarating Don’t Explain, carrying a spellbinding performance by Diana. The song was penned by Billie and Arthur Herzog Jr, the idea forming after Billie’s husband, Jimmy Monroe, came home one night with lipstick smeared over his collar. Diana’s interpretation is haunting, heavenly even, and sends cold shivers down your spine, especially when seeing her sing the song live in concert. Though never commercially released, Don’t Explain was subsequently issued on promotional 45s.

The stark effect of Strange Fruit, a song used in the film in which Billie describes how she saw a black man hanged from a tree following a vicious racist attack from the Ku Klux Clan, is delivered by Diana in an icy but magnificently compelling performance. Hauntingly atmospheric in tone, she stretches herself vocally, becoming totally immersed as her voice drips with a genuine and raw emotion.

Another major highlight is the stirring, gutsy God Bless The Child, which first appeared as the B-side to Good Morning Heartache. Diana once again loses that occasionally angelic sound to deliver a strikingly husky, lower-register performance that’s just mesmerising. In Billie’s autobiography, she recalled an argument with her mother over money, and during this heated exchange, her mom said, “God bless the child, that’s got his own.” Feeling enraged, this led to Billie turning the line into a starting point for the song. Billie’s original version was later honoured with the Grammy Hall of Fame Award in 1976.

Strange Fruit was written in the late 1930s by teacher Abel Meerepol, originally as a poem, about the lynching of African-Americans. Lynchings occurred in the south primarily, but there were several others in various regions. The writer, Abel, set Strange Fruit to music and, along with his wife and singer Laura Duncan, performed it as a protest song against racism in many venues across New York, including Madison Square Garden. Years later in 1978, Billie Holiday’s definitive reading of the song was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, as well as later being listed in the Songs of the Century, by the Recording Industry of America and the National Endowment for the Arts.

My Man (Mon Homme) is just triumphant. The beauty and essence of soul in Diana’s own sound pours out on this exalting number. Her diction, phrasing and enunciation are so precise, and the more complex inclines of the song are mastered to perfection. A deep, aching sadness is conveyed by Diana here, the sense of isolation and choked-up emotion cleverly executed. The slow-burning piano-led arrangement grows into a rousing climax when she’s backed by an overflow of strings and horns. Diana remains remarkably understated, never quite letting go yet retaining the sombre, despairing mood and sounding more powerful than ever. The song originated in France and was first recorded in the English language by Ziegfield Follies singer Fanny Brice. Though many contemporary artists have tackled My Man, it’s Diana Ross’ heartbreaking rendition that easily ranks among the definitive versions of the song.

There are occasional lifts in mood from the doom and gloom, mainly on the swinging, sassy Gimme A Pigfoot And A Bottle Of Beer. A song screaming out about fun and rebellion, Diana sounds completely authentic here in a song that came from the 1930s. She’s also able to showcase her lower and upper vocal range. There’s a playful and joyous take on Gershwin’s Love Is Here To Stay while ‘T’ain’t Nobody’s Business If I Do is a defiant statement that still has an air of fun about it. An eight-bar Vaudeville blues song written by Porter Grainger and Everett Robins in 1922, this became an early blues standard that, as well as by Billie Holiday, was also recorded by the likes of Bessie Smith, Mississippi John Hurt and Jimmy Witherspoon, among others.

The considerably restrained anguish in Diana’s voice on You’re Mean To Me balances the sparkling Fine And Mellow. A Billie Holiday original from the late 1930s, the song depicts the harsh treatment of a woman at the hands of her abusive man. Starting with loud, blaring horns, the brash song covers drinking, gambling and sex, wrapped in an exciting jazz-blues arrangement. Diana’s vocal approach is like a dignified swagger, sounding dynamic yet restrained throughout, lagging behind the beat with style.

Her interpretation of What A Little Moonlight Can Do is slightly more bubbly, but she conveys the yearning that was so true to Billie’s style on I Cried For You. The latter is another swinging tune recorded in an upbeat style, the jazz musicians excelling with their rhythm section and piano and horns work. Absolutely stunning and one of the very best tracks recorded for the soundtrack is the haunting and spine-tingling Lover Man (Oh Where Can You Be). Both sombre and mellow in Gil Askey’s beautiful arrangement, Diana displays the true depth in her vocal delivery here, giving a goosebump-ridden performance. Written by Jimmy Davis, Roger ‘Ram’ Ramirez and James Sherman, Billie Holiday’s rendition was another to be honoured with the Grammy Hall Of Fame Award in 1989.

Much the same could be said for her raw, bluesy sound on Lady Sings The Blues, another song by Billie, which she wrote with jazz pianist Herbie Nichols. There’s also astounding reworkings of Gershwin’s The Man I Love and All Of Me, the latter recorded numerous times by artists including Bing Cosby, Louis Armstrong, Sarah Vaughan, Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra. One of the songs where Diana sounds remarkably like Billie is on the stark You’ve Changed. Recorded by Billie on her Lady In Satin album, Diana’s interpretation is one of the strongest of the soundtrack and one of the most masterful and haunting.

The Lady Sings The Blues soundtrack was recorded under the supervision and guidance of Gil Askey, who had every faith in Diana’s ability to bring Billie Holiday to the silver screen: “We already knew what Diana could do with Billie’s stuff from what she did when we gave her My Man to sing years earlier on that Bob Hope special. So we weren’t at all reluctant or worried about her ability to sing jazz. I gave her a tape of eighteen songs we intended to use in the movie, songs Billie Holiday had recorded. Every night, she’d lie in bed with her earphones on and listen to that music, falling asleep with the music of Holiday in her head. She did this for months.”

Some of the nifty, talented jazz musicians at work on the soundtrack had already worked with Billie; they included guitarist John Collins and bassist Red Holloway.

The complete track listing in running order for the Lady Sings The Blues soundtrack is as follows: The Arrest, Lady Sings The Blues, Baltimore Brothel, Billie Sneaks Into Deans And Deans, Swinging Uptown, ‘T’aint Nobody’s Business If I Do, Big Ben, C.C Rider, All Of Me, The Man I Love, Them There Eyes, Gardenias From Louis, Cafe Manhattan, Had You Been Around, Love Theme, Any Happy Home, I Cried For You (Now It’s Your Turn To Cry Over Me), Billie And Harry, Don’t Explain, Mean To Me, Fine And Mellow, Lover Man (Oh Where Can You Be), You’ve Changed, Gimme A Pigfoot And A Bottle Of Beer, Good Morning Heartache, All Of Me, Love Theme, My Man (Mon Homme), Don’t Explain, I Cried For You, Strange Fruit, God Bless The Child, Closing Theme. The songs are interspersed with dialogue from the film.

The soundtrack sold in excess of three hundred thousand copies within its first week of release and shot up the US Pop chart to #1. It was a triumph for all concerned, especially Diana, who was now at a positive turning point in her career. The film changed many critics’ perceptions of Diana Ross from here. It seems inconceivable the album was never nominated for a Grammy, but this indeed was the case. However, it received the recognition it deserved by scooping album of the year at the annual American Music Awards. And at the 45th Annual Academy Awards ceremony in 1973, Diana was pipped for best actress by Liza Minnelli for her performance in Cabaret. Nonetheless, Diana’s nomination led to thirty film offers, which she was forced to refuse, as she was signed to Paramount for at least one other film.

She graced the cover of several magazine covers (mainly relating to Lady Sings The Blues), which included Jet, Ebony, Thursday, Soul, Rap!, Cash Box and Life.

On New Year’s Day 1973, Diana provided the half-time entertainment at the Rose Bowl, performing a version of Love Is Here To Stay.

The following month, she appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine under the heading ‘The Diana Ross Story’ then a few months later on Sepia with it reading ‘Diana Ross: Will she win an Oscar?’, then on the cover of TV Week in March, shared the cover alongside singer/actress Ann Margret on Photoplay magazine, appeared on the Soul Train TV show in April before gracing the cover of Blues & Soul magazine again.